California Water History in a Minute – Subsidence

- Aug 1, 2025

- 4 min read

The California Department of Water Resources (DWR) recently released a document on subsidence and how to stop it. When groundwater is pumped, particularly from wells deep underground, the ground above can sink, as the clays between the aquifer and the ground surface compress. This phenomenon of the ground surface sinking is called subsidence.

Subsidence has been a problem in California ever since we began using large capacity wells to do irrigation. The DWR document describes the history this way:

“From 1926 to 1970, an area in the Central Valley southwest of Mendota had documented subsidence of more than 28 feet. Construction of the Central Valley Project began in the late 1930s to address water supply and distribution in California’s Central Valley. The introduction of Central Valley Project surface water imports via the Friant-Kern and Delta-Mendota Canals in the 1950s, and Central Valley Project and State Water Project surface water imports via the California Aqueduct in the 1970s, significantly reduced groundwater reliance, initiated groundwater level recoveries, and slowed—and even reversed—subsidence in some areas of the San Joaquin Valley [emphasis added].

However, expansions of agricultural acreage and drought periods between 2000 and 2023 coincided with reduced surface water availability [emphasis added], resulting in increased groundwater pumping, which resulted in accelerated subsidence rates of more than 1.0 ft/year in parts of the San Joaquin Valley and more than 0.5 ft/year in parts of the Sacramento Valley.”

DWR does not describe what caused reduced surface water availability during that period, but we know that major environmental regulations implemented in the mid-1990s diverted millions of acre feet of surface water away from farms and people and sent it to the ocean. Because groundwater was unregulated, much of that diverted surface water was replaced by groundwater. It really is not a surprise that subsidence again emerges as a major problem to be addressed.

The problem is real and, in this document, DWR outlines Best Management Practices for how to slow it down and ultimately eliminate it. Unfortunately, the only way to stop subsidence is to stop lowering groundwater levels and in fact increase those levels above what DWR describes as “critical head.” Critical head is the groundwater level below which permanent compaction begins. See this video for more information on critical head.

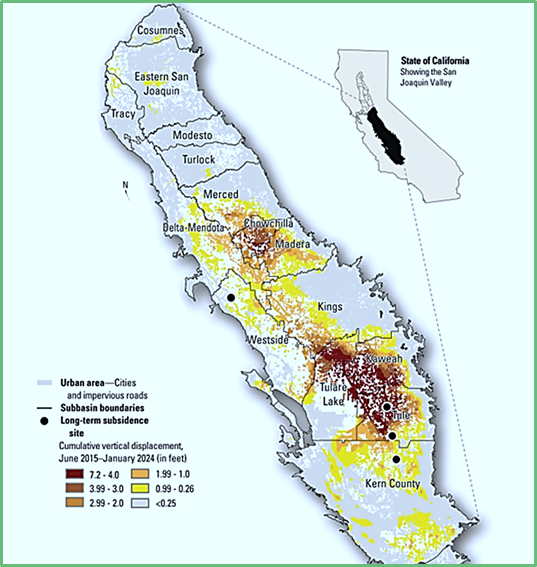

As you can see from the map below, the dark areas have subsided between 4-7 feet in just the last nine years with the rate of subsidence showing no signs of slowing up. The subsidence issue is the most challenging problem facing a number of Groundwater Sustainability Agencies (GSAs). To simply stop pumping groundwater would cause massive economic, environmental (dust, weeds) and societal problems. What GSAs need to do is greatly increase their knowledge of where, and at what groundwater level, wells are producing in their areas. Without that knowledge, the pumping restrictions necessary to address subsidence will be broader and more restrictive than they need to be.

While we can observe the effects of subsidence from above ground, there is a lot we do not know about what is actually going on underground. There is an urgent need for much more data about what is happening underground. DWR has provided good guidance in this Best Management Practice document and has a role to play in helping to provide funding and expertise to assist the GSAs in getting the data necessary to develop effective but efficient subsidence management plans.

The government should also recognize that regulations that diverted surface water away from farms and people significantly contributed to this problem and addressing those regulations to get more surface water as well as facilitating the maximizing of local wet year water for recharge is also part of the fix. The Water Blueprint for the San Joaquin Valley is on the right track with its latest release today.

Water Blueprint for the San Joaquin Valley

Urges Federal Action on Water Infrastructure

The Water Blueprint for the San Joaquin Valley today announced it has sent formal letters to both the San Joaquin Valley Congressional Delegation and U.S. Secretary of the Interior Doug Burgum, urging significant federal investment in California’s water infrastructure. These letters underscore the urgent need to advance immediate and longer-term solutions to the Valley’s growing water supply crisis and advocate for strategic investments that will protect agriculture, rural communities, and the environment.

The Blueprint’s outreach follows the recent passage of the One Big, Beautiful Bill Act, which includes $1 billion in federal funding for specific types of water infrastructure investments —a critical first step toward addressing an estimated $12 billion funding need for projects of these types necessary to modernize California’s water system.

Key Points from the Letters:

Acknowledgment of Federal Support: The Blueprint thanked Valley lawmakers for securing $1 billion in the One Big, Beautiful Bill Act, recognizing it as a vital down payment on broader water infrastructure needs in California.

Call for Additional Investment: The letters emphasize the need for further federal funding to support conveyance repairs on the Friant-Kern Canal, Delta-Mendota Canal, San Luis Canal, and California Aqueduct, as well as expanded water storage projects.

Economic and Environmental Urgency: Citing the UC Davis study Inaction’s Economic Cost for California’s Water Supply Challenges, the Blueprint highlighted the potential loss of up to 9 million acre-feet of water annually by 2050, with projected economic damages of up to $14.5 billion and the fallowing of 3 million acres of farmland.

Appeal to Secretary Burgum: The Blueprint urged the Department of the Interior to prioritize California’s water infrastructure in federal planning and funding decisions, and to support collaborative, science-based solutions that benefit both people and ecosystems.

A Voice for the Valley

“The Blueprint represents a united voice for the San Joaquin Valley—farmers, water agencies, communities, and conservationists—working together to secure a sustainable water future,” said Eddie Ocampo Chair of the Water Blueprint. “We are grateful for the progress made, but we must keep pushing forward. The future of our region depends on it.”

Learn more about the Water Blueprint for the San Joaquin Valley at WaterBlueprintCA.com.

Geoff Vanden Heuvel

Director of Regulatory and Economic Affairs

Comments